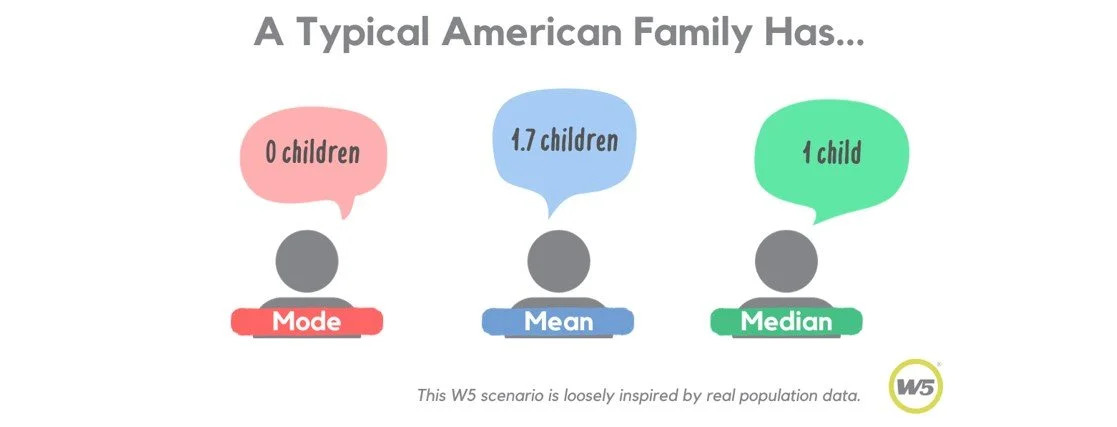

A House, a Dog, and 1.7 Children: Central Tendency in the Marketing Context

By Kelsey Howell

Marketing research often seeks to understand typical behavior. As researchers, we think to ourselves that a new product should appeal to the “typical” in-category consumer, not an outlier. For example, we believe revenue projections should be based on typical earnings, not deviations from the norm, and so on.

The challenge this presents is that there is no one-size-fits-all way of truly defining typicality.

The unsolved nature of this “typicality” problem, though, is actually a blessing, even if it seems a curse. Multiple answers mean adding multiple layers of complexity to our understanding. This is where the three commonly used measurement models of central tendency come into play—each conveys unique information about a marketing situation, but we are commonly taught to use them singularly, selecting one that feels like a best fit and disregarding the other two. At W5, however, we see greater potential through including all three in our final share outs.

So let’s have at it and let mode, mean, and median present their arguments below…

Mode is the simplest measure of central tendency, as it simply measures the most frequent response given.

The mode model is most useful for data with no measurable “distance” between possible responses. You can’t place ice cream flavors on a scale from “vanilla” to “pistachio,” for example. It will be impossible to average out or find the “middle” between those flavors.

The pitfall of using mode is that it obscures statistical trends beyond the first-place finisher. In the above example, mode misleadingly suggests the typical American is childless because the count of zero-child families is higher than 1, 2, or 3+ child families individually. Aggregating responses that represent a larger trend or faction (i.e., “families with children”) can be a useful counterbalance.

W5 typically reports the mode by charting responses from most to least common.

Marketing situations that would be summarized well by mode:

· Consumers’ preferred flavor of ice cream

· Awareness of B2B financial service providers

· Respondent area of residence

Mean, or Average can be found with data that does exist along a consistent scale such as age (in years), count (in whole numbers), spend (in dollars), etc. To find the mean, first add together all responses, then divide the total equally across all respondents.

Mean is most useful when there is a desire to take information to scale. For example, a school may scale the amount of food it purchases to an assumption of 1,000 families with “1.7 children” each. This will result in a total amount of food that covers everyone. Mean is excellent for making projections, which is why it gets so much use in market research!

When describing the behavior of a typical individual, however, mean is less consistent. For example, I think we can all agree that no family has “1.7 children.” Outliers in the data, such as families with five or more children, also have a disproportionate impact on the mean. Graphing the distribution of a data set can be useful for finding outliers and determining whether they should be included in analysis.

W5 typically reports the mean in the last row(s) of a data table, where applicable.

Marketing situations that would be summarized well by mean:

· Average lifetime value per commercial printing service client

· Click-through rate across a social media campaign

· Expected number of product returns over the holidays

Median also requires data points to have measurable distances between them. To find the median, sort all responses from lowest to highest value (i.e., 0 children, 1 child, 2 children, etc.), then find the data point at the halfway mark between them all.

Median is most useful at describing an ordinary respondent within the sample, as it has the ability to “see through” unequal data distributions. For example, the average cost of a wedding in 2016 was $25,720, but the median cost was under $15,000. Weddings within specific cultural traditions (such as Hindu weddings) may be significantly more expensive than the median but are performed by fewer U.S. residents.

This understanding of a typical individual can be used to appropriately target marketing campaigns, as going for the average may actually alienate the majority. A large gap between mean and median may indicate a need for segmentation to capitalize on smaller high-value groups.

Medians are less useful for making predictions than the mean/average however, as they do not simulate the lower and higher end of expected outcomes. Median may also fluctuate more than mean as a sample builds due to the “middle” point moving every time a response is added. This can result in choppy and inconsistent results when comparing medians across demographic or behavioral subgroups. Looking at the overall data distribution remains a helpful check.

W5 typically reports the median in the last row(s) of a data table, where applicable.

Marketing situations that would be summarized well by median:

· Customer satisfaction level

· Website loading time

In Conclusion

Our key takeaway in the realm of central tendency measurements is that more often than not, the answer to the "mode, mean, or median" conundrum lies in embracing all three, at least to some extent.

Each contributes a distinctive angle for exploration and their utility depends on factors including question design, research goals, and broader contextual clues within the data set. When navigating the statistical landscape, each model brings something valuable to the table, enriching our understanding of typicality in diverse ways.

Happy researching!

Want to learn about how W5 would utilize this mindset with your brand, organization, or product, or just chat with fellow insights enthusiasts about the ways central tendency plays out in our shared world of marketing research? Contact us today!